Resources

Compliance

Business Travel Risk Map for 2026

Download the 2026 business travel risk map with country-specific risk classifications. Get clear threat assessments for every destination to protect traveling employees and fulfill duty of care.

What do your clients think about WorkFlex?

Listen to it yourself

idealo

"WorkFlex has helped us tremendously in reducing administrative costs and also administrative work. All the paperwork done in one tool, so we don't have to manually type contracts."

Forto

"The use is incredibly easy. Employees simply sign up. We don't handle A1 certificates ourselves because everything runs through WorkFlex. We also don't issue any other documents. With one click, the process is released and then it just runs smoothly."

Autoscout

"I found the collaboration with WorkFlex to be excellent. Even in the preparation, I was supported at all times. And all questions were answered in the shortest possible time."

Explore the articles

Podcast: Creating a better CX Community

Posted Worker Compliance: Guide to registration requirements and digital transformation

Posted Worker Compliance: Guide to registration requirements and digital transformation

The management of posted worker compliance is at a critical turning point. As cross-border work continues to grow across Europe and the world, employers face mounting pressure to effectively manage their posting compliance. The stakes are high – Luxembourg's recent enforcement actions resulting in €9M in fines for employer non-compliance in just one year demonstrate authorities' increasingly serious approach to enforcement1.

The European Commission has recently proposed the adoption of a unified posted worker portal that signals both an opportunity and a warning. While promising to reduce the administrative burden of posted worker notifications by up to 73%, the new digital system will create unprecedented transparency and opportunity of enforcement for authorities. Organizations managing cross-border work face a clear choice: modernize their compliance approach now or risk exposure in an increasingly digital enforcement landscape.

This article examines how the posted worker compliance landscape is changing, what these changes mean for HR and global mobility teams, and why waiting to adapt is not an option. Most importantly, it provides a clear path forward for organizations looking to turn this challenge into an opportunity for efficient, future-proof compliance management.

1 Centre commun de la securite sociale (2023). Rapport Annuel 2023.

1. What is a Posted Worker notification?

A posted worker notification is a mandatory registration requirement for employees working temporarily in EU or EEA countries. Required by the Posted Workers Directive (“PWD”), these notifications inform local authorities when workers enter their jurisdiction, enabling them to monitor compliance with local labor laws and protect workers' rights. Not all business trips require such a notification to be submitted. However, generally, this is triggered by a cross-border service provision. Please note that each country defines at the national level what is considered as a “service provision”, therefore activities are treated differently in each country and different exemptions might apply. As an example, Belgium even requires a PWD notification to be submitted for workations. Further, some countries only require a PWD notification to be submitted if the posting company is based in the EU, while in other countries it is required even for companies based in third countries. Employers must register their employees through country-specific portals before the trip begins. With different procedures and requirements across national legal systems, and significant penalties for non-compliance, these notifications have become a crucial consideration for any organization managing cross-border work in the EU and beyond.

2. The current reality of Posted Worker management

2.1. The purpose and importance of Posted Worker notifications

For labor authorities, posted worker notifications serve as a crucial enforcement tool that enables them to protect both workers and fair market competition. These notifications provide authorities with essential visibility into cross-border work activities, allowing them to:

- Monitor compliance with local employment conditions, ensuring workers receive proper working conditions, notably including wages and appropriate working hours

- Verify social security coverage remains valid during the posting period

- Prevent social dumping and maintain fair competition in local labor markets

- Ensure posted workers receive all entitled protections in the destination country

- Track proper documentation for tax and legal purposes

2.2. Complexity of Posted Worker registration systems

HR and global mobility managers in global organizations face a daunting task: managing posted worker notifications across 31 different systems2 throughout Europe. For each destination, HR teams must learn to navigate a different notification portal, understand specific local requirements, maintain separate login credentials, and manage distinct submission processes. This creates a nearly impossible task without dedicated resources or technological support.

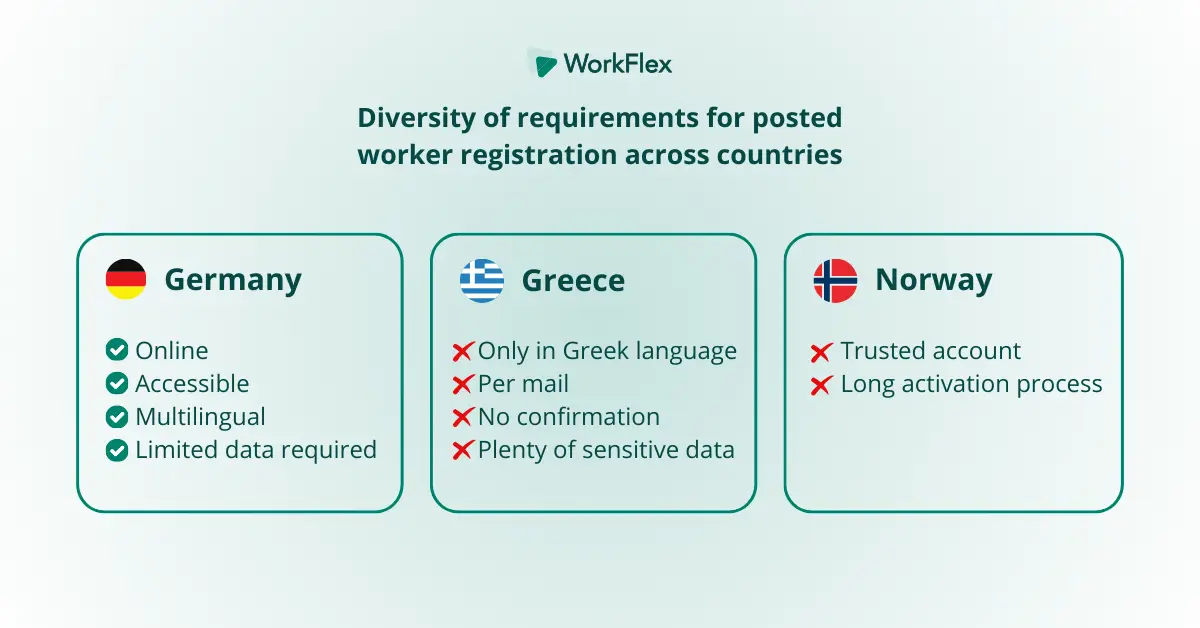

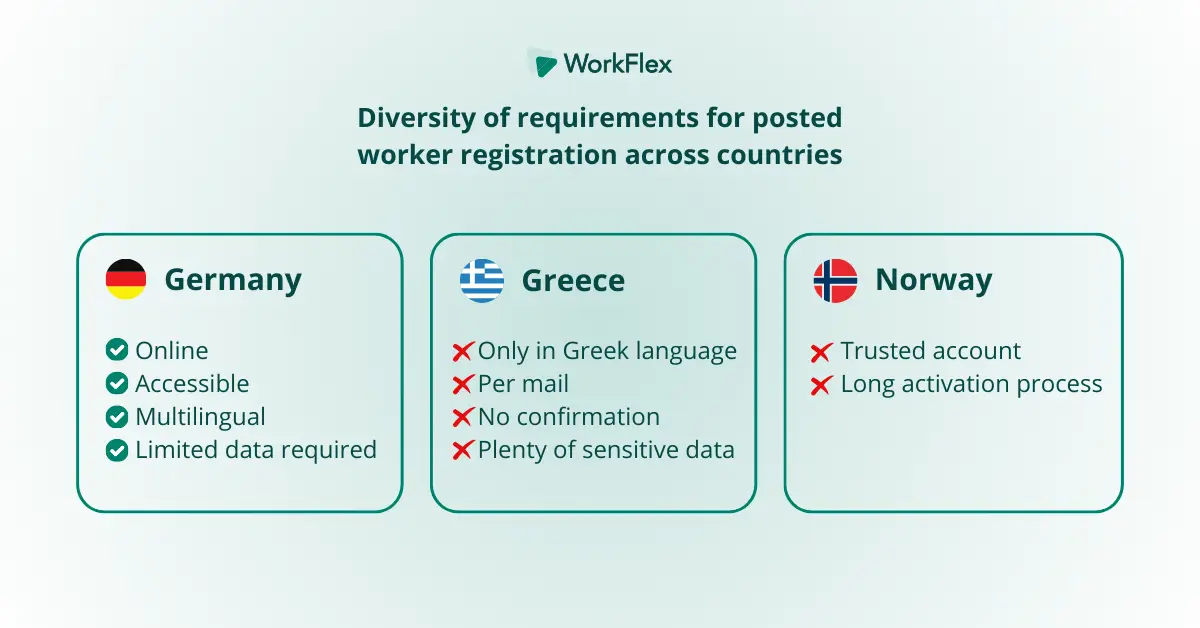

To illustrate this complexity, let's examine three national systems that demonstrate the varying levels of difficulty HR teams face in the image below. Germany stands out with an easy-to-use system to register posted workers, while Greece provides medium-level complexity, and Norway – highly complex posted worker registration process.

2 27 EU member countries and 4 EFTA countries (Norway, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Iceland)

2.3. Administrative burden of registering Posted Workers

This complex landscape translates into significant administrative burdens for employers. Current studies indicate that businesses typically spend between €150-200 per posting on administrative costs alone, with processing times varying dramatically by country - from 21 minutes in Estonia to 61 minutes in Italy and up to 87 minutes in Greece per posting.

The administrative workload breaks down into three main categories:

- Data collection (17%)

- Data entry (33%)

- Document management (51%)

To put this in perspective, the German mechanical engineering industry, with its 205,000 registered postings annually, spends a minimum of €31 million yearly on administrative costs alone.

2.4. Compliance risks and consequences of ignoring Posted Worker registration requirements

Despite the significant administrative burden, companies cannot afford to ignore these requirements. The consequences of non-compliance can be severe. Luxembourg recently demonstrated authorities' serious approach to enforcement by imposing €9M in fines for non-compliance in just one year.

The severity of consequences varies by country:

- Some countries initially provide warnings

- Others have strict regulations with immediate economic sanctions

- Fines for missing or late notifications (e.g. Switzerland imposes up to €5,000)

- Additional sanctions for working condition violations can exceed €50,000

- Service bans can prevent business operations for up to five years

- Companies may be published on shared labor authority lists, affecting reputation

- Practical consequences include workplace access denial, particularly in Scandinavian countries

- Reputational damages as an employer and as a company (e.g. in Switzerland major infractions will be published in an openly accessible online list)

{{download-box}}

3. The European Commission's new Posted Worker portal initiative

3.1. Why is the Posted Worker registration portal proposed

The growing complexity of managing 31 different notification systems has not gone unnoticed by European institutions. In recognition of the significant administrative burden this place on businesses, while also acknowledging the challenges it creates for effective enforcement, the European Commission has proposed a unified solution: a single portal for all posted worker notifications across the EU. It is crucial to emphasize that this is a proposal and therefore it is not guaranteed at all yet, whether it will be adopted or not. Further, we must notice that the proposal only concerns the notification system. Specific national legislations will still be applicable even if such a proposal will be adopted. This notably concerns sanctions and consequences in case of violations, as well as particular requirements, meaning whether a notification will be required or not for specific activities performed by employees temporary working abroad. The Commission's proposal aims to streamline the process for businesses while simultaneously enhancing authorities' ability to protect workers' rights and ensure compliance.

Key features of the portal will include:

1. Single multilingual platform

- Access in all EU official languages

- Standardized terminology across countries

- Unified interface for all submissions

2. Standardized processes

- Common data entry formats

- Unified submission procedures

- Standardized documentation requirements

- Consistent notification timelines

3. Data storage and reuse

- Information retained for future submissions

- Employee data stored securely

- Company details saved for repeated use

- Historical posting records maintained

4. IMI System Integration

- Connection to Internal Market Information System

- Enhanced data sharing between authorities

- Streamlined verification processes

- Integrated compliance checking

3.2. Benefits and their implications: The two sides of Posted Workers' digital transformation

The Commission's proposed portal promises significant efficiency gains, but each improvement comes with new considerations for organizations managing posted worker compliance.

Streamlined data entry and enhanced visibility

The new system promises a 73% reduction in submission time through standardized forms and simplified processes. This will have as an immediate practical consequence, the creation of unprecedented transparency. Therefore, authorities will have immediate access to standardized, comparable data across all postings, making pattern recognition and compliance monitoring more effective than ever.

Centralized data storage and cross-border sharing

The ability to store and reuse information will eliminate duplicate data entry and reduce administrative burden by 25%. This centralization also means that authorities across countries can easily share and cross-reference information through the Internal Market Information System (IMI), enabling coordinated enforcement actions.

Standardized documentation and increased scrutiny

The elimination of country-specific documentation requirements will significantly simplify the submission process. Increased standardization also means that compliance gaps become immediately apparent, as authorities can more easily compare documentation across different postings and organizations.

Cost reduction and enforcement efficiency

While the elimination of administrative fees and reduced processing time will lower costs for businesses, it also reduces barriers for authorities to conduct systematic compliance reviews. What previously required manual investigation and coordination will become automated and instantaneous.

This digital transformation means that organizations must approach their posting management with new considerations. Those that have historically struggled with compliance, underestimated its value, relied on manual processes, or taken a decentralized approach may find themselves exposed in this new transparent environment. The efficiency gains of the proposed portal could be significant, if at all introduced, but they will come with the expectation of higher compliance standards and more rigorous enforcement.

4. Preparing for the digital transition of Posted Worker registrations

4.1. A timeline for change

The European Commission's proposal marks a significant step forward, but at the moment it is a simple proposal that might not lead to any new legislation. In any case, even if adopted, the transition will be gradual. While a specific launch date is yet unknown, we can expect a 13-month adoption process followed by a 2-3 year implementation period. With voluntary adoption by member states, organizations will likely need to manage both the new unified portal and existing national systems until at least mid-2026. Furthermore, it remains unclear how EFTA countries will engage with the proposed changes.

However, this implementation timeline presents both a challenge and an opportunity. While the unified portal is still some time away, the shift toward digital enforcement is already underway. Organizations that wait for full implementation before modernizing their approach risk falling behind in two critical areas:

- Managing current compliance requirements across 31 systems

- Preparing for the increased transparency of the future digital landscape

4.2. Building Future-Ready Compliance

While organizations would appreciate the unified portal, compliance obligations demand attention today and will continue to do so in the future. Organizations must continue to navigate complex requirements across multiple jurisdictions. As discussed previously, the proposal only concerns the notification modality, but does not affect at all any other aspect related to PWD compliance:

Documentation management

Beyond basic notifications, organizations must maintain comprehensive records of employment contracts, posting agreements, social security certificates, and other essential documentation. These records must be readily accessible for potential audits and meet specific national requirements.

Local law compliance

Each posting must comply with host country regulations, notably including:

- Equal pay requirements

- Working time regulations

- Health and safety standards

- Industry-specific requirements

Multiple system management

During the transition period, organizations will need to manage both existing national systems and the new unified portal, creating additional complexity in documentation and compliance tracking.

The key to managing these obligations, while preparing for the digital future lies in automation. Modern compliance management systems can help organizations:

- Handle current multi-system requirements efficiently

- Build digital-ready processes for the future

- Ensure consistent compliance across jurisdictions

- Create audit-ready documentation trails

4.3. Automation in action: The WorkFlex approach

WorkFlex's solution demonstrates how automation can transform posted worker management from a burdensome manual process into a streamlined, future-ready operation. The system integrates seamlessly with existing business travel processes to:

- Automatically assess the applicability of notification requirements when travel is booked

- Generate and submit required notifications

- Manage documentation across jurisdictions

- Ensure compliance before travel begins

- Maintain comprehensive audit trails

This automated approach not only addresses current challenges but positions organizations for success in the coming digital enforcement landscape. By implementing such solutions now, organizations can:

- Reduce current administrative costs

- Ensure consistent compliance across systems

- Build digital-ready processes

- Prepare for increased transparency

- Create scalable, future-proof compliance management

The transition to digital enforcement is inevitable. Organizations that act now to modernize their compliance approach will not only manage current requirements more efficiently but will be well-positioned for success in the increasingly digital future of posted worker management.

{{download-box}}

Assignment Compliance 101: A Guide to Effective Expat Management

Assignment Compliance 101: A Guide to Effective Expat Management

Are expat assignments giving your HR team headaches? Between immigration paperwork, tax compliance, and social security requirements, it's easy to feel overwhelmed. Let us show you how automation can change that.

We invite you to join our webinar "Assignment Compliance 101: A Guide to Effective Expat Management" where our expert panel will share insights on streamlining your assignment management process.

📣 Speakers:

- Pieter Manden LLM MBA – Co-founder WorkFlex

- Dorothee Schweigard – Director Compliance Research Center, WorkFlex

- Anna Luisa Grebe – Lead Visa & Assignment, WorkFlex

In this session, our experts will:

✔️ Break down essential compliance requirements for expat assignments

✔️ Share proven strategies to overcome common challenges

✔️ Demonstrate how automation transforms assignment management

Plus, you'll see WorkFlex in action through a live demonstration and have the opportunity to get your questions answered during our interactive Q&A session.

Is your work-from-anywhere policy compliant?

Is your work-from-anywhere policy compliant?

➡️ What does it take for a company to remain fully compliant when employees go on work-from-anywhere trips? Is an A1 certificate and visa enough? What measures should HR and travel teams take to ensure the employer's duty of care is fulfilled when employees travel?

Our experts, Pieter Manden, LLM, MBA, Co-founder of WorkFlex, and Brock Dale, Senior WorkFlex Consultant, guide you through the critical aspects of compliant work-from-anywhere policy management.

In the session, you learn about key things to consider when creating and managing your work-from-anywhere policy. 🧐

Cross-border workforce compliance trends for 2025

Cross-border workforce compliance trends for 2025

As 2025 approaches, it’s crucial to stay ahead of the evolving cross-border compliance landscape. 💡

Join us for an insightful webinar where global mobility experts will share findings from a comprehensive survey of 300 companies, shedding light on emerging trends in cross-border workforce compliance.

➡️ Key topics to be covered:

- Emerging trends in cross-border employment and employee mobility, including business travel, workations, commuters, matrix managers, expatriates, virtual assignments, and remote work.

- In-depth analysis of business travel trends and associated compliance challenges.

- Best practices and insights on the most widely adopted work-from-anywhere policies and their impact on global mobility

➡️ Speakers:

- Christine Kraft, Senior Manager Global Mobility, Vialto Partners

- Paul Bennett, Co-founder and CEO, PerchPeek

- Pieter Manden LLM MBA, Co-founder WorkFlex

Stay informed and gain practical insights to optimize your global mobility programs for 2025 and beyond. 🌎

Compliance for work-from-anywhere trips: Why an A1 certificate is not enough

Compliance for work-from-anywhere trips: Why an A1 certificate is not enough

Do you think that an A1 certificate is all you need for a compliant workation? Let us prove you wrong!

In our exciting webinar, we uncover the hidden risks that many overlook. Dorothee Schweigard, our compliance expert and head of the Compliance Research Center at WorkFlex, and Sandro Günaltay, our Senior WorkFlex consultant, will explain the most important factors that are essential for a safe and compliant workation.

Find out why an A1 certificate is just the beginning and how you can protect your employees comprehensively when they go on work-from-anywhere trips. Join us and delve deep into the world of workation compliance!

🗣️ Language: German

Insights from 10.000+ Remote Work Stays in over 200 Companies

Insights from 10.000+ Remote Work Stays in over 200 Companies

Can local labour law become applicable to remote workers enjoying a workation?

Can local labour law become applicable to remote workers enjoying a workation?

Dr. Martina Menghi is the Manager for Trust & Employer Compliance at WorkMotion. She is an Italian attorney at law, holding a double degree in law (Italian and French). Prior to joining WorkMotion in August 2022, she worked at KPMG Law in Germany for four and a half years, focusing on international labour law and posted workers obligations, which was also the topic of her PhD thesis.

Pieter Manden LLM MBA is the Co-Founder of WorkFlex and former Head of Trust & Employer Compliance at WorkMotion. He is a Dutch certified tax lawyer specialising in compliance around modern mobility. Pieter has 13 years of professional experience with PwC in the Netherlands and Germany. He was Director responsible for the PwC Germany’s Remote Work proposition prior to joining WorkMotion in January 2022.

I - Executive Summary

It deserves upfront mentioning that the existing labour law regulations have been adopted several years ago and have not been shaped around workations. Rather, they were designed having business travellers and posted workers in mind. Workationers’ are not only a new phenomenon, their situation is also fundamentally different given the lack of a business purpose in the destination country.

After having analysed the applicable rules, we have come to the conclusion that there is good and bad news. Starting with the bad: in principle, there are indeed some labour law provisions of the destination country that might theoretically become applicable. The good news, however: it is extremely unlikely that these provisions will in practice really be applied by a local judge.

The reason for this is twofold. First, only a judge in the destination country can determine that so-called “overriding mandatory provisions” in the destination country are applicable. This implies a litigation where the local judge actually considers itself competent. This last point is unlikely, given that a home country employment contract is in place, the home country remains the habitual place of employment and the stay in the destination country is limited in duration.

Second, according to EU law the “hard-core provisions of the country of habitual employment” remain applicable also to international situations. Hard-core provisions essentially concern the following aspects such as minimum wage, working hours, and paid leave. This means that the aforementioned judge would only be able to apply “overriding mandatory provisions” in the destination country on topics which do not make part of these fundamental, hard-core provisions in the home country. It is safe to say that this is so unlikely, that in practice local labour law provisions will have no impact on workations.

{{download-box}}

II - Abstract

This article deals with the complex question of determining which employment law is applicable to remote workers enjoying Workations within the EU. Pursuant to Regulation 593/2008, the principle is the parties’ choice. However, even if employment contracts regularly specify which law is governing the employment relation, in cross-border situations the employee benefits of special protection. In fact, working abroad might trigger the application of the employment law of the destination country, notably concerning two categories of rules: the provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement (1) and the overriding mandatory provisions (2). Unfortunately, both categories are not defined in the EU legislation and national courts are left to define them according to national law.

Provisions belonging to the first category, mainly considered as those on minimum wage, health and safety and working hours, are those of the state in which or, failing that, from which the employee habitually carries out his/her work in performance of the contract. In case it is not possible to identify the habitual place of work, residual criteria apply.

Further, provisions belonging to the second category must always be applied by national courts, regardless of the law applicable to the employment contract. Legal scholars often disagree on categorisations and interpretations of which rules belong to this category. However, the European Court of Justice confirmed that these provisions must be interpreted strictly. The provisions of the destination country concerning some specific matters are “overriding” for posted employees during postings, applicable regardless of the law governing the employment contract and regardless of the posting duration. However, a number of arguments speak in favour of not equating remote workers on Workations to posted employees. In particular, the constitutive elements of posting are lacking from our remote work scenarios, i.e. service provision and host entity.

However, given the fact that the posted worker directive defines the “hard-core” of posted employees’ protection, it makes sense to look closer at those provisions and ask whether these would be applicable to remote workers as well, given their protective nature. Even though it is important to take into account that common rules exist at the EU level for all these hard-core matters, a closer look to these topics lead us to the conclusions that the most potentially problematic aspects might be the salary, given the fact that this is the matter where the highest discrepancies exist among Member States. At the same time, it is worth noting that there is no evidence that hard-core rules would be considered as overriding provisions for remote workers in the destination country.

To summarise: even if a risk of application of some destination country employment law provisions exists, it appears strongly mitigated in case of workations.

III - Position Paper

Can local labour law become applicable to remote workers enjoying a workation?

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to highlight the criteria to take into account when performing a risk assessment concerning the applicable employment law to remote workers temporarily working from abroad. These are employed in a State (Home State) and during a so-called “Workation” (an employee benefit, a combination of work and vacation) are working in another one (Host State). We will refer to them simply as “remote workers” throughout this paper, according to the definition below - even though this term does not reflect the temporary character of the international stay, which is clearly an important aspect. Remote work occurs when employees find themselves in a situation where the below cumulative requirements are met:

- The employee works outside the Home State on a temporary basis (where “temporary” is generally being defined as below 183 days per calendar year);

- The employer has allowed the employee to temporarily work remotely outside the Home State;

- The trip does not have any business reason or purpose, i.e. there is no initiative nor need of the employer at the basis of the trip, the trip is entirely privately driven;1

- The employee does not give up the residency in the Home State.

The paper focuses on the legal framework in EU law, given the fact that there is a legal source and the majority of WorkMotion clients are European.

It does not intend to analyse national specific rules, if these exist.3 Some national laws are only mentioned through examples and illustrations of practical implementations. However, given the current legal framework, it should be possible to identify some common rules for remote workers on the territory of Member States.

The rules that will be analysed were adopted before the Covid-19 Pandemic and the “explosion” of remote work during and following this. As a result, the rules were never designed with the current reality in mind, which leads to an ambiguous situation. At the same time, clearly remote work did to a certain degree also exist prior to the pandemic. Take Mario as an example: he is an associate at a big German law firm dealing with mergers, projects that usually take months. The negotiations of a new project start after Mario has booked his vacation to Greece. If he is lucky enough to still be allowed by the law firm to leave for vacations, instead of having to cancel it at the last minute, what would be the most likely outcome?

During the vacation in Greece, Mario would most likely have to constantly be looking at his mobile phone and reading and sending emails, in order to catch up and understand what is going on during his (physical) absence from the office. This might raise many questions: would such a situation potentially justify the application of Greek employment law? Is he considered on a business trip, or does he even qualify as a posted employee? It seems that these questions were not considered as vital, before the advent of remote workers.

Potential Conflicts of Law

Not surprisingly, in situations characterised by some degrees of “internationality”, such a cross-border dimension (employment in the Home State, temporary remote work in the Host State) presents potential law conflicts. One of the main risks is notably that the Host State’s employment law becomes applicable. This has some very relevant practical implications. Amongst others, the following questions need to be answered: which minimum wage standards must be applied to the employees, those deriving from the law of the Home State or the Host State? Which law determines the maximum working hours, the minimum rest periods and the annual holidays?

It is therefore crucial to identify, with certainty, the applicable law to the employment relation. In EU law, it is possible to seek the relevant answers in Regulation (EC) No 593/2008 of 17 June 2008 on the law applicable to contractual obligations (Rome I) (hereafter “the Regulation”). This is an instrument of “universal application”, meaning that any law specified in it shall be applied, whether or not it is the law of a Member State, as stated in its Article 2.

The Regulation’s general objective, as announced in Recital 16, is legal certainty in the European judicial area. The foreseeability of the substantive rules applicable to contracts must not be affected.

1. The parties' choice (Art. 8 (1))

As a preliminary observation, the employment contract belongs in principle to the private law sphere. This means that, like in all private law contracts, the parties’ will is crucial and therefore they are able to choose which law shall be applicable.

Employment contracts usually specify which law shall govern it, so this is expected to be the most common scenario.

However, the employment contract is indeed a peculiar one, where one of the two parties (the employee) is facing a situation of weakness if compared to the other party (the employer). If we consider the negotiation power, it is clear that the employee is de facto in the position of having less room for manoeuvre and flexibility than the employer.

Therefore, the Regulation adjusts this unbalanced situation, by providing the employee with some further protection. It establishes, in Article 8 (1) as a general rule, that an individual employment contract shall be governed by the law chosen by the parties. However, it also specifies that such a choice of law may not have the result of depriving the employee of the protection afforded to him/her by provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement under the law that, in the absence of choice, would have been applicable to the contract.

It becomes decisive to answer the following question: how to identify the law that, in the absence of choice, would have been applicable to the contract? Some authors refer to this law as the “objective law” of the contract.

2. Problem 1: identify the habitual place of work (Art. 8 (2))

The main criterion is laid down in in Article 8 (2) of the Regulation: “(t)o the extent that the law applicable to the individual employment contract has not been chosen by the parties, the contract shall be governed by the law of the country in which or, failing that, from which the employee habitually carries out his work in performance of the contract.” Throughout the text we will refer to the “country in which or, failing that, from which the employee habitually carries out his work in performance of the contract” simply by using the expression “habitual place of work”.

The same provision also clarifies that the country where the work is habitually carried out shall not be deemed to have changed if the employee “is temporarily employed in another country”.

It is relevant from the beginning to notice that a regular workation, meeting the criteria defined in our introduction, is very unlikely to change the habitual place of work of the employee.

In this context, it is essential to define the adverb “temporarily”.

According to Recital 36 of the Regulation, “work carried out in another country should be regarded as temporary if the employee is expected to resume working in the country of origin after carrying out his tasks abroad.”

Article 8 has as objective to ensure, as far as possible, compliance with the provisions protecting the employee that are laid down by the law of the State in which that employee carries out his/her professional activities.

For the sake of completeness, it is worth mentioning that the “habitual place of work” is not the only criterion provided by the Regulation. In fact, in some cases it is not possible to determine it. Art. 8 (3) states that, in such cases, “the contract shall be governed by the law of the country where the place of business through which the employee was engaged is situated.” Further, according to Art. 8 (4) “(w)here it appears from the circumstances as a whole that the contract is more closely connected with a country other than that indicated in paragraphs 2 or 3, the law of that other country shall apply.”

It is important to point out that these last two paragraphs (3) and (4) are residual to paragraph 2 and therefore the criterion of the country where the employee is “habitually” working is the privileged one, having priority over the others and to be interpreted in a broad sense.

Only if it is not possible to identify the country where the work activity is habitually carried out, it will be admitted to look at the place of business through which the employee was engaged and at the closest connection to another country.

According to the CJEU, “it was the legislator’s intention to establish a hierarchy of the factors to be taken into account in order to determine the law applicable to the contract of employment.”

Therefore, in our analysis we will mainly focus on the dualism between, on one hand, the “country where the employee habitually works” and, on the other, “country where the employee is temporarily on Workation”. We assume that ideally it shall be possible to identify, and if necessary to distinguish, between the two countries.

The core notion lies undoubtedly in the definition of the adverb “habitually”. The question is how to identify it? Unfortunately, there is no definition in the Regulation. In some cases, it seems easier to define it than in others.

In the lack of a definition of “habitually” in the Regulation, we are facing a notion characterised by “flexibility”. Such flexible notions are actually quite common in the EU law and have the advantage of being used in several legal contexts, enabling the Court of Justice (”CJEU”) to fulfil the notion, by giving an interpretation of their content and their limits.

It might be at first sight disappointing, but, according to the Court, there is no duration that can be taken as a standard reference. This might seem as a disadvantage, but it is actually comprehensible. The identification of the “habitual place of work” is not limited to a matter of countable and definable duration.

It is not possible to answer straightforwardly to the question “How long does an employee have to work in a place before it becomes his/her habitual place of work?”, simply because time worked in a given workplace is not the only factor enabling the assessment of the place of employment.10 There are many other factors to be taken into account.

The CJEU indicated some useful criteria11for identifying the country of habitual place of work performance, including:

- the actual workplace (in the absence of a “centre of activities”, the place where the employee carries out the majority of the activities);

- the nature of the activity carried out;

- the elements that characterise the employee’s activity;

- the country in which or, failing that, from which the employee carries out his/her activity, or an essential part of it, or receives instructions on his/her tasks and organises his/her work activity;

- the place where the work activity tools are placed;

- the place where the employee is required to present himself/herself before carrying out his/her duties or to return after having completed them;

The Court of Justice specified that the notion of “habitual place of work” “must be interpreted as meaning that, in a situation in which an employee carries out his activities in more than one State, the country in which the employee habitually carries out his work in performance of the contract is that in which or from which, in the light of all the factors which characterise that activity, the employee performs the greater part of his obligations towards his employer.”

Furthermore, there can be situations in which the place where the employee performs the greater part of his/her obligations towards the employer is particularly complex. This is illustrated by case law before the CJEU. The Court took the opportunity to specify first of all that in case of a contract of employment under which an employee performs for his employer the same activities in more than one Member State, it is necessary, in principle, to take account of the whole of the duration of the employment relationship in orderto identify the place where the employee habitually works. Failing other criteria, that will be the place where the employee has worked the longest.”

However, this consideration is intended to play a role only where it will not be possible to use the other criteria listed above, such as the actual workplace, the nature of the activity carried out and so on.

It has been pointed out, as a general rule, that occasional tele-work should in principle not affect the identification of the habitual workplace. For example: an employee that habitually works in Germany and for a 6 month-period during pandemic, worked full-time from another EU Member State (e.g. Austria). Whether his/her employment contract stipulates that German law is applicable or not, German law will govern the contract.

Once the country of the habitual place of work of the employee has been identified, it is necessary to look at the provisions that, according to the law of this country, cannot be derogated from by agreement, since those will have to be applied to the employment contract of the employees, even if these employees work remotely in another country for some time.

3. Problem 2: identify the provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement (Art. 8 (1))

A recent decision16 of the CJEU offers a very comprehensive overview on the law applicable to the employment contract, which is worth summing up.

The Court ruled that the correct application of Article 8 of the Rome I Regulation requires the following steps to be accomplished:

- In a first step, that the national court identifies the law that would have applied in the absence of choice (namely: that of the habitual workplace) and determine, in accordance with that law, the rules that cannot be derogated from by agreement;

- In a second step, the national court has to compare the level of protection afforded to the employee under those rules with that provided for by the law chosen by the parties;

- If the level of protection provided for by those rules is greater, those same rules must be applied.

Unfortunately, the Regulation does not give a definition of “provisions that cannot be derogated from”. This means, as confirmed by the Court, whether a provision belongs or not to those that cannot be derogated, will have to be decided according to national law: “The referring court must itself interpret the national rule in question.”

A case-by-case analysis becomes necessary. However, the CJEU had the opportunity in several judgements to clarify, in practice, some guidelines. According to the Court’s interpretation, the provisions in object “can, in principle, include rules on the minimum wage”.

Further, rules concerning safety and health at work, protection against unlawful dismissal, as well as rules on working hours are some relevant examples, coming from national jurisprudences, of rules that have been considered as “provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement” by national courts.

Since it is extremely unlikely that the Host State will become the habitual place of work for remote workers, this second problem is just as unlikely to materialise. The provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement (Art. 8 (1)) applicable to remote workers, will be in fact the ones of the Home State.

Once the Home State has been identified as the habitual place of work and its provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement, is it possible to completely exclude the application of the Host State employment provisions?

4. Problem 3: identify the overriding mandatory provisions (Art. 9)

Article 9 of the Regulation refers to the “overriding mandatory provisions” of the Host State: “The Regulation shall not restrict the application of the overriding mandatory provisions of the law of the forum.”

“Because of their importance for the State that has enacted them, such provisions must be observed even in international situations, irrespective of the law governing the contract under the normally applicable choice-of-law rules of the Regulation.”

Their respect is regarded as crucial by a country for safeguarding its public interests, such as its political, social or economic organisation. They are applicable to any situation falling within their scope, irrespective of the law otherwise applicable to the contract under the Regulation.

The difference between, on one hand, overriding mandatory provisions and on the other, those analysed under the previous section, namely the “provisions that cannot be derogated from by an agreement”, based on Art. 8, is actually not of immediate comprehension.

Unfortunately, the Regulation does not give a definition of overriding mandatory provisions (likewise to the previous article dealing with the provisions that cannot be derogated). Again, a case-by-case analysis is necessary.

The only specification from the legislature is to be found in Recital 37 of the Regulation, where it is stated that the two categories of rules shall “be distinguished”. In particular, those of Art. 9 should be construed more restrictively: “Considerations of public interest justify giving the courts of the Member States the possibility, in exceptional circumstances, of applying exceptions based on public policy and overriding mandatory provisions”.

These two categories of provisions have complementary purposes: Art. 8 seeks to avoid that the general principle of “freedom of choice” of the law applicable to the employment contract will diminish the protection of the employee working in the Host State. Art. 9 aims to enable the Host State to safeguard its public fundamental interests, by applying its core overriding rules to all contractual relations executed on its territory, regardless of the applicable law.

In other words, the application of provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement can be avoided (for instance because the habitual place of work is not in the Host State), while the overriding mandatory provisions are always applicable.

As a derogating measure, Art. of the Rome I Regulation must be interpreted strictly. National courts, in applying it, are not intended to increase the number of overriding mandatory provisions applicable by way of derogation from the general rule set out in Article 8 (1) of the Regulation.

“In considering whether to give effect to the provisions, regard shall be given to their nature and purpose and to the consequences of their application or non-application”.

It has been observed that due to its exceptional nature as “derogating measure”, the practical importance of Art. 9 should not be overestimated.31It is possible to identify overriding mandatory provisions in different legal areas (A). When it comes to employment law, there are currently not numerous available examples (B). Provisions concerning posted workers are considered to be part of this category. However, we will argue that remote workers are not to be considered as posted employees (C).

A. General examples of overriding provisions

As stressed out, it is not easy to establish whether a provision is mandatory or not. In some cases, it is directly stated in the provision itself. Some illustrations can be found in different areas of the law, such as family law, property law or public law. Unfortunately, this is seldom the case.

Indeed, the CJEU's decisions “giving effect to foreign overriding mandatory provisions, as allowed by Art. 9 (3)” are particularly rare.34 Failing such an indication, it is a matter of interpretation, to be decided by examining the content of the rule and its underlying policy under domestic law.

It is worth mentioning the prevailing opinion in the German academic interpretation stating that “a clear distinction should be made between the mandatory norms pursuing public goals and those protecting individual interests”.

On the one hand, there are rules interfering with contractual law (named after the German verb “eingreifen”, to interfere, (“Eingriffsnormen”)), in order to pursue public interests. On the other hand, there are rules aiming to preserve and even re-establish a balance between the contract parties and the interests of some specific categories of individuals (e.g. the employees).

This methodology leads to the conclusion that employee's protection does not fall under the scope of overriding mandatory provisions.

This is not only a scholars’ view, it has been confirmed by German courts as well. In this sense, the protection of employees would not be considered as within the scope of Art. 9. A renowned case law did not apply it to a dismissal litigation. The German Federal Labour Court (“Bundesarbeitsgericht”), refused to apply a number of German rules protecting employees against abusive dismissal.

“It is highly debatable whether Art. 9 also covers mandatory rules that are designed to protect certain categories of individuals, in particular weaker parties, such as consumers, employees, tenants, commercial agents, franchisees, etc.”

However, there are also scholars promoting a different approach, according to which “rules aimed at the protection of individual interests can also qualify as overriding mandatory provisions”41 by arguing that “although Art. 9 refers to the safeguarding of public interests (...) this provision should not be construed as implying an a priori exclusion from its scope of all norms aimed at the protection of individual interest”.

Beyond the different argumentations, the interpretative dispute is still open. This shows that for the moment it is not (yet) possible to answer unilaterally and unequivocally the following question: which norms fall under the definition of overriding mandatory provisions?

B. Employment law overriding provisions

As mentioned previously, currently there are not many guidelines in this area and each national court is thus able to establish which national measures must be considered as overriding.

At the national level, a decision of the French State Council (“Conseil d’État”) is considered as “the leading case related to overriding mandatory provisions”.44It stated that a company employing more than 50 employees in France must establish an employee representative committee, even if the lex societatis of the company was Belgian law.

The Supreme Court of Luxembourg ruled that the jurisdiction of the Luxembourgish courts was mandatory regarding employees working on Luxembourgish national territory. Such jurisdiction could not be derogated by a choice-of-court agreement.

At the European level, two significant decisions were adopted by the CJEU,46 where it was recognised that “the overriding reasons relating to the public interest which have been recognised by the Court include the protection of workers.”

It is in theory conceivable that a country has “a crucial interest in compliance with a specific overriding mandatory provision in the area of employment law”.48 However, even if an overriding mandatory character can be recognised to employment law rules, it is important to determine to what extent. In fact, they should always be interpreted in compliance with EU law.

According to the most extensive interpretation of Art. 9, national rules having as objective to protect the employee, should be regularly regarded as applicable overriding provisions, even if the employee works in the Host State only on a temporary basis. This would be quite impractical and does not really seem to be supported by any case law at the moment. Even though it cannot be excluded that such an argument might be invoked in the future, this interpretation would clash with the Regulation's wording, according to which they are to be interpreted strictly.

Lastly, it is also interesting to question whether the two categories of provisions - resulting from Art. 8 and Art. 9 - can be cumulatively applied. In other words, whether a provision can be at the same time considered as “non derogable” and “overriding”.51 The discussion seems open and once again, different opinions coexist.52 However, given the Recital 37 suggesting “to distinguish” between them, it seems that a national provision either belongs to one category, or to the other.

C. The (unease) relation with posting of workers rules

According to Recital 34 of the Regulation: “The rule on individual employment contracts [notably the criteria in Art. 8] should not prejudice the application of the overriding mandatory provisions of the country to which a worker is posted in accordance with directive 96/71/EC of 16 December 1996 concerning the posting of workers in the framework of the provision of services”(hereafter: “the Directive”).53In other words, regardless of the law applicable to the employment contract, when employees are posted to a Member State, this has to ensure their protection on its territory. As a result, its provisions concerning specific matters shall always prevail and be applied, for the entire posting duration. These matters are listed in Art. 3 of the Directive,54 constituting the “hard core” of posted employee’s protection.

Through a nucleus of mandatory rules for minimum protection to be observed, the aim is to ensure fair competition among service providers, i.e. the employers posting workers in the territory of another Member State. The promotion of the transnational provision of services requires in fact a climate of fair competition.

The respect of posted employees' hard-core protection in the Host State guarantees that the freedom to provide services is exerted in compliance with EU law. This is ensured by avoiding competition distortions, which would take place if the services providers were able to exploit different levels of posted employees protection.

Due to their protective character in the posting context, the hard core provisions of the Host State are to be considered as overriding mandatory provisions for posted employees.

The wording used in the German implementation of the Directive also qualifies the hard core provisions as mandatory.57 The provision clearly expresses its intention to be applied independently from the law of the contract.

Since 2014,58 posted workers must be registered in the Host State. The aim of the registration is to notify the national labour authorities about the presence of posted employees on the national territory and facilitate controls and inspections.

It appears therefore necessary to answer the substantial question whether remote workers are to be considered as posted employees or not. At the moment, the discussion appears controversial and there is no absolute answer, neither in the legislation nor in case law.

However, strong arguments lead to the direction of a negative answer. Two arguments are substantial,61 while the third one is formal.

1. Remote workers are not providing a cross-border service

The provisions referred to as mandatory by the Regulation are those of the country to which a worker is posted. Arguably, this means in the Host State where they are temporarily assigned by the employer. This is not the same situation occurring in case of a Workation. In fact, the remote workers are not “assigned”, they rather travel exclusively because of their personal interest. For this argument to apply, it is fundamental to exclude that the remote worker has any business reason to travel to the Host State. However, no tangible business purpose can be identified in case of remote workers: the trip is entirely privately driven.

2. There is no service recipient in the Host State

The circumstance that the remote worker will be performing activities providing a service on behalf of the Home Company in favour of a host entity might have a relevant impact on his/her qualification as “posted employee”. If the employee will travel for business purposes, the trip may not be considered solely privately driven any longer.

However, no host entity can be identified in case of remote workers.

If a posting is taking place, there is no doubt that the hard core terms and conditions of the Host State will be applicable to the employee, according to Art. 3 of the Directive.

3. Registration formal requirements

Beyond the above-mentioned substantial arguments, there are also practical considerations. Inter alia, several Member States’ posted workers registration forms systematically require a host company to be provided, as well as the “scope of service”. If these fields are not completed, the registration is rejected and/or considered incomplete. In some cases, it cannot even be submitted, as the online portals prevent the registration if some fields are left empty. Further, in some cases, the scope of service has to be selected from a dropdown list. Not surprisingly, the private interest of employees is not listed amongst the possible services options.

In summary, the lack of two constitutive elements of posting (1. and 2.), in combination with the considerations on the registration requirements (3.), are clear indicators that posting rules, including the hard core rules ex. Art. 3 (1) of the Directive are not applicable to remote workers.

Still, this interpretation is shared but not unanimous and clarity through legislation or case law is urgently needed.

Until then, we can only speculate which national employment law provisions will be considered as overriding for remote workers. National courts will have the last word, mainly on a case-by-case approach.

Not even the CJEU appears in the position of questioning whether, in practice, a national law can be invoked as overriding: “it is not for the Court to define which national rules are “overriding mandatory.”

The CJEU is nonetheless entitled “to review the limits within which the courts of a Contracting State may have recourse to that concept.” As such, it is not excluded by a proportionality check.

It is not possible to predict how the CJEU will rule, so here again there is room for speculation. In the context of remote workers, free movement of citizens might also be invoked in the future. This has proven to be one of the favourite arguments of the CJEU, of great importance for European integration, as far as taking place in the established legal limits, notably provided that the employee does not become an unreasonable charge for the Host State. Citizens of the Union shall enjoy the rights and be subject to the duties provided for in the Treaties. They shall have, inter alia: the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States.65

Managing and mitigating risks

Once having given credits to the interpretation according to which remote workers are not to be qualified posted employees, it is possible to hypothesise which national provisions can be considered as overriding and therefore be applicable to them in the Host State. As a starting point, it seems reasonable to take as reference the hard core protection rules for posted employees themselves.66 We will try to find out whether the hard core rules would be applicable also to remote workers, even if we tend to exclude their qualification as posted employees.

By using a “a contrario” methodology, it can be argued that if the Regulation explicitly refers to the mandatory character of posted employee core rules, it was not the legislator's intention to include under this kind of protection the other categories of workers, i.e. the employees that are not posted, but rather belong to a different categories, like, for instance, remote workers.

However, these rules have a protective nature and therefore, it is worth questioning whether they might be invoked as “overriding provisions”.

Two general remarks must be made here: first, the hard core provisions are often matters directly regulated by EU law, as it will be illustrated.69 This mitigates the risks.

Secondly, Art. 9 is applicable in active litigation. A national court will have to determine which national overriding provisions will be applicable to pending cases.

We might observe, this is quite unlikely to happen, in practice, in case of remote workers on Workations.

The remote worker is temporarily abroad by using a benefit granted from the employer, without being assigned. Therefore, the probability for the employee to take legal actions in the Host State against the employer might be quite low. At the same time, unforeseeable circumstances might always occur and the possibility cannot be completely excluded. Further, in principle, even in case there is no claim from the employee, it is important to notice that a number of issues, such as worker safety, maximum hours, or employment discrimination are in many EU Member States considered as “public enforcement,” in the sense that their application is to be taken by national governmental authorities. Each national authority is responsible for either taking action to enforce the rules within its territorial boundaries.

Therefore, it shall be argued that even if the employee does not submit any claim, in case of inspections and controls, employment authorities might, at least in abstracto, question whether the national standards have been respected in the Host State.

De facto, the longer the employee stays in the Host State, the longer is likely to occur an inspection or a control and/or a litigation take place. On the other hand, one might also argue that inspections and controls at work are implemented “randomly”. However, on average, it is quite unlikely they will concern remote workers, working remotely from an airbnb, hotel or at a family house, as empirical evidence shows.

Even when it comes to posted workers controls, for instance, these mainly concern the sectors that are “sensitive” from a social dumping perspective and as such are more frequently objects of national inspections and compliance checks. The best example is the construction sector. Not surprisingly, this is also the sector where the majority of postings arise. To give an illustration, if in the framework of the same projects an engineer is posted from the Polish Home Company to the Netherlands to take part to business meetings with the Dutch client and 5 employees are also posted to carry out their activities on to the construction site, it is more likely than the 5 employees will be controlled by labour authorities rather than the first one.

( a ) maximum work periods and minimum rest periods;

Before analysing whether working hours are to be considered as “overriding provisions”, it is worth stressing out that this problem should not be overestimated. Since working hours are the object of an EU directive,76there are not, with a few exceptions, significant discrepancies amongst the Member States.77 The “European working week” seems to be aligned, on average, at 40 hours per week.78

Even taking into account that there still are differences at the collective bargaining agreement (CBA) level, the average difference oscillates between 35.6 and 40 weekly hours. In addition, it is also unclear whether these agreements are applicable to remote workers in the first place (e.g. non all EU Member States systems have erga omnes effects for CBAs).

Furthermore, when looking at working hours there is quite a discrepancy between theory and practice, as can be seen inter alia in the Euro Surveys on “actual working hours per week”, which show the difference among “statutory” and “effective” working hours worked by the employees in the Member States.

Therefore, working hours might not be such a big concern, in spite of legal uncertainty concerning their mandatory character.

It is interesting to notice a decision recently adopted in France, where the weekly working hours are the shortest in the EU, namely 35/w. The French Court ruled that working hours are not overriding, but rather provisions that “cannot be derogated”. If we look back at the interpretation of mutual exclusion of the two categories, one might reach the conclusion that working hours are mandatory for posted employees, but not for remote workers.

( b ) minimum paid annual leave;

Like maximum work periods and minimum rest periods, this matter is regulated in the EU Directive 2003/88.

According to Art. 7 of this directive, Member States shall grant at least four weeks per year to the employees. Contractual agreements might extend the minimum legal requirement. Even if, like for working hours, there might be differences among Member States, it seems reasonable to scale down the biggest concerns.

Given the fact that minimum paid holidays are usually accumulated per month but have to be taken on a yearly basis, the problem appears quite abstract. It seems rather impractical to admit that the remote worker might claim such entitlements during Workations in the Host State, when the stay lasts significantly less than one year.

( c ) remuneration, including overtime rates;

This is probably the most delicate aspect, given the fact that it is where the biggest differences among Member States exist.

Someone observed that in most all jurisdictions of the world, rules on wage/hour tend to be mandatory and reaching everyone, even guest workers only temporarily working in a host country.

Nevertheless, this argument seems in principle quite simplistic and often contradicted by the reality of an interconnected and globalised world, where business trips, especially of short durations, are still, in spite of the pandemic, quite common.

If, for instance, an employee hired in Milan, Italy, under an Italian employment contract, travels on a 3-day business trip to Stockholm, Sweden, in order to negotiate a contract with a potential client, it is quite unlikely to imagine he/she will invoke the Swedish salary application before Swedish courts, even if this might be higher than his/her in the Home State. Further, it is unlikely that the Swedish court will recognise his/her right to have access to the national minimum wage.

Such a scenario would even raise concerns when it comes to legal certainty, if everytime there is a business trip, employees were able to fully invoke standards of the Host State. As mentioned, fragilization of legal certainty is exactly what the Regulation seeks to avoid.

According to the CJEU, ‘provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement’ can, in principle, include rules on the minimum wage. Once more, if these rules are covered by Art. 8, they would not be considered as overriding according to Art. 9 of the Regulation.

( e ) health, safety and hygiene at work;

Scholars do not agree when it comes to qualifying occupational health and safety. According to some, “local rules always apply due to the territorial principle”.85 According to another interpretation, health protection is actually part of provisions that cannot be derogated, based on Art. 8.

The discussion around this topic is a good legal exercise, however it remains in the end quite abstract in the EU: health and safety at work is in fact already an harmonised topic, where the standards are regulated in several pieces of EU legislation, such as the Directive of 12 June 1989 on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work (89/391/EEC).

( f) protective measures with regard to the terms and conditions of employment of pregnant women or women who have recently given birth, of children and of young people;

For the categories in object, the need for protection is somehow even bigger, since they are not only employees, but also in a particularly weaker situation.

Given the fact that the initiative of Workations lies exclusively in the employees initiative, even if it shall not be excluded a priori, it is hard to imagine remote workers in such situations, able to invoke this kind of protective rules in the Host State.

Here again, the matters are regulated at the European level and minimum standards are shared by EU Member States, as stated in Directive 92/85/CEE.87

( g ) equality of treatment between men and women and other provisions on non-discrimination.

Non discrimination is a “classic” EU topic. The EU rights are build around the non-discrimination principle. Several directives have been adopted to fight against illegitimate discriminations,89 and Member States commonly share the minimum standards.

As illustrated, Member States have a limited discretion in legiferating around the “hard-core” aspects of the employment relations. Therefore, even if differences exist, notably concerning salary standards, their scope should not be exaggerated.

In practice, companies usually have thresholds calculated on the base of duration also for registering posted employees, even if in several countries, posting registration obligations apply as of posting day one. It is a matter of risk evaluation. Therefore, it makes sense to advise companies operating in sensitive sectors, where inspections are most likely to occur (e.g. construction) to be compliant with registration obligations from the very beginning. For companies posting mainly so-called “white collars” a more extensive and tolerant approach might be the best one (e.g. registration only of postings exceeding a certain duration).

This premise is necessary to highlight how, even if there is no doubt that rules concerning posted employees obligations are better defined and established than those concerning remote workers, risk assessment always plays a crucial role. In other words, it is hard to imagine that for companies adopting a 100% compliant approach would always represent the best solution. Compliance checks imply in fact costs and time.

Conclusions

Taking into account the above, it is worth noting that EU Member States have a legitimate interest, in compliance with EU law, in guaranteeing the protection of workers on their territory. This can be achieved by imposing the mandatory observance of some local rules. However, in order to invoke the application of national law, a sufficiently close degree of connection with the Host State is required.

The rationale behind the posted workers Directive and its rules on minimum protection is to facilitate the freedom to provide services.

The question is whether and to what extent the Host State might need to apply national employment law provisions to the remote worker. In this context, it is also to be taken into account whether the remote worker is able to harm competition, or interact with the labour market of the Host State.

As a general rule, employers should evaluate whether Workations might trigger an impact on the applicable law to the employment relation. Local employment laws could in principle, in some cases, override the contractual wording and contractual choices. To summarise, whenever Problem 1 is solved, i.e. when it is possible to clearly identify the Home State as the country where the employee habitually works, looking at Problem 2, becomes redundant. In fact, there is no need to look at the “provisions that cannot be derogated”, because they overlap with the ones of the State of habitual place employment, i.e. the Home State.

However, as we saw, it is in principle always relevant to look at Problem 3, i.e. overriding mandatory provisions.

It is unfortunately not possible in abstract terms, to predict with certainty which provisions might be considered applicable due to their “overriding mandatory” character.

In several cases, the EU legislation is not specific enough or we are facing a lack of clear provisions. Clarifications at the legislative and judicial level would be more than welcomed. In the meanwhile, there is still much room for speculation and different interpretations. However, nothing prevents that in the future the authorities' practices might change and evolve in different directions. New EU legislation might be adopted, filling the current legal gaps and providing different answers than those given so far.

Lawmakers need to adjust existing rules to a new reality. This is an authentic need not only for employment, but for all legal areas where there might be significant consequences for remote workers, starting from taxation.91 Once again, reality is overtaking legal provisions.

This still remains an unexplored territory and therefore, it becomes crucial to adopt a cautious approach and not extend too much a “permissive” interpretation of the existing rules. At the same time, if the law does not explicitly forbid something, it does not make necessary sense to automatically assume that it is incompatible with EU law.

Even if some prudence is necessary, the risks might be mitigated in several cases, if taking into account the Workation context. Since it cannot be a priori excluded that some national employment provisions might be applicable in the Host State, a safe approach might be the

preferred choice. Nevertheless, we definitely tend to support the argument that in situations such as Workations it is, for practical reasons, very unlikely to be the case.

.avif)

€1 million in savings: How Telenor mitigates business travel compliance risk with WorkFlex

.avif)

€1 million in savings: How Telenor mitigates business travel compliance risk with WorkFlex

🔎 ABOUT TELENOR

Leading telecom company willing to modernize management of tax risk

Telenor is a telecom and digital services company from Norway with more 170 years of history and 11,000 employees globally. The company conducts business in 25 countries, mainly in the Nordic region and Asia. With its significant international presence, the company generates substantial cross-border employee movement. In the last year alone, Telenor has records of 13'500 trips, of which 5'500 were international business trips.

With the great volume of business trips, Telenor's team saw improvement opportunities in business travel compliance management:

The key item on my agenda since I joined Telenor four years ago has been to modernise how we manage tax risk across the group and mobility in general, and business travel in particular.

Liv Lundqvist, SVP and Head of Group Tax at Telenor

🔥 CHALLENGE

Unmanaged business travel created serious permanent establishment and tax compliance risks

Telenor faced several critical challenges in managing its international business travel:

- Taxable presence risks: The way Telenor conducted travel activities represented the risk of establishing taxable presence or even permanent establishment in countries abroad. "It became very clear to me that left unmanaged, our employees could then lose the protection provided by the 183 days rule in the tax treaties," revealed Liv Lundqvist.

- Manual case-by-case processing: Business travel compliance wasn't managed centrally or in a structured manner at Telenor. While expat assignments had clear governance, short-term business trips and non-standard cross-border mobility were handled differently across legal entities, all done manually on a case-by-case basis, often with help of several external vendors.

- Inconsistent documentation practices: There was no central approach to applying for A1 certificates or Posted Workers Directive documentation. HR colleagues in some of the entities applied for A1 certificates when business trips exceeded certain days, but there was no one structured approach.

- Duty of care concerns: The company wanted to ensure employees traveling for Telenor always had proper documentation in hand, reflecting their strong duty of care philosophy rooted in their Scandinavian headquarters culture. As explained by Annemarie Bunschoten-Schraven, Global Mobility Project Manager at Telenor: "We don't want them to be caught in a certain country without the right visa, or without the right Social Security documentation."

🎉 SOLUTION

Partnering with WorkFlex to automate and centralize compliance management

After a thorough RFQ process, Telenor team selected WorkFlex. Their choice was influenced by several key capabilities:

- Comprehensive risk assessment: WorkFlex's global compliance engine evaluates all core business travel-related risks including tax, labor law, visa, Posted Workers Directive requirements, and more, providing clear guidance on compliance needs.

- Seamless system integration: WorkFlex integrated seamlessly with Telenor's existing travel booking system Egencia and HRIS Oracle. That ensured comprehensive compliance coverage without disrupting established workflows.

- Automated documentation generation: WorkFlex platform automatically handles A1 certificates, Certificate of Coverage, and Posted Workers notifications, removing the manual case-by-case approach that previously required external vendor involvement.

- Adaptive implementation support: WorkFlex's speed and flexibility proved essential for enterprise-scale adaption. The WorkFlex team stood out with rapid adaptation capabilities and short communication lines enabling quick resolution of any challenges.

"During the RFQ process, it became very clear to me that we needed to partner with a modern vendor who could support us through this transformation journey. You share our interest in ensuring that it is the system that will handle certain tasks and hopefully remove some manual work, either by us or by our external advisors."

- Liv Lundqvist, Senior Vice President and Head of Group Tax

🎯 BENEFITS

€1 million in business travel compliance risk mitigation

Telenor has so far achieved substantial benefits through WorkFlex implementation:

- Major risk mitigation: Looking at the volumes of business travel and potential fines, the solution easily leads to approximately €1 million in savings by mitigating compliance risks.

- Rapid 3-month implementation: Telenor had completed all legal data privacy requirements, technical integration, and employee communication within just three months, demonstrating the efficiency of WorkFlex's implementation process.

- Enhanced operational efficiency: Instead of case-by-case involvement of tax vendors for basic assessments, Telenor now knows all business trips managed by WorkFlex have proper risk assessments, A1 and PWD compliance in place, allowing their specialised tax vendors to focus on other tasks like shadow payroll.

- Elevated global mobility function: The centralized business travel compliance has increased the visibility of Telenor's global mobility team as an expertise center, helping them renew all cross-border mobility offerings and better support talent development initiatives.

One of the success factors that we were actually able to go live was the fact that WorkFlex is super-flexible and adaptable. The fact that the mindset of the people working at WorkFlex and their technical knowledge and really having this tech first approach helped... There was never a "No" as an answer.

– Annemarie Bunschoten-Schraven, Global Mobility Project Manager

How EGYM scales compliant work-from-abroad with WorkFlex

How EGYM scales compliant work-from-abroad with WorkFlex

🔎 ABOUT EGYM

A global fitness tech leader with a truly international team

EGYM provides fitness and health facilities with connected equipment and digital products that integrate with third-party solutions. It also offers subscription-based corporate fitness and wellness solutions.

- 850+ employees

- 60+ nationalities

We’re an international organization, and our teams frequently ask to work abroad - either to visit family or to travel, so the demand is high.

— Liska Kürten, Talent Acquisition & People Operations Partner, EGYM

🔥 CHALLENGE

Balancing employee flexibility with compliance risks

Before introducing WorkFlex, EGYM didn’t allow employees to work abroad. The demand was there - employees from over 60 nationalities regularly asked to spend time with their families abroad or to combine travel with work - but the risks felt too high:

- Compliance uncertainty: HR team had limited knowledge about tax, social security, labor law, data security, and permanent establishment risks.

- Operational concerns: Managing mobility without automation would be complex and resource-intensive.

- Need for visibility: HR team required a structured way to see who was working abroad and when.

“Global mobility at scale is complex and resource-intensive. We needed a comprehensive, automated solution that keeps us compliant while supporting employee flexibility.”